|

Reading two very different books has set me to a bit of thinking. One was Mariana Mazzucato's The Value of Everything and the other Tom Devine's To the Ends of the Earth.

Mazzucato focuses primarily on how we define value and how this in turn defines what constitutes economic development. She rightly notes how this essential debate was deliberately closed off by the marginalist (or neo-classical) economics developed in the 1890s. This left us with no tool other than to accept that if a good, or an activity, had a price, then by definition it had value. So asset stripping, speculative investment and rent seeking are all 'valueable' purely as they can command a price. This is now so embedded in modern economics teaching that it is hard to remember the debates that dominated the profession in the period 1750-1890 (including Adam Smith) as to what was, and what was not, productive (and thus of value). Devine, at one glance, has no engagement with this debate. His book is a fascinating take on migration from Scotland and does an excellent job of debunking Prebble's lugubrious focus on the Highland Clearances. Most of the Scottish diaspora was voluntary, mainly a product of seeking to escape the low wages that were endemic in Victorian Scotland by people with some assets (note that here I am not arguing that the clearances were anything but an act of organised brutality which has left a permanent scar on Scotland) and often marked by both leaving and returning (unlike say nineteenth century Irish migration). The key issue is the impact of those low wages. Not only did this drive migration it had a catastrophic effect on the development of Scottish industry. By the 1860s, Scotland had an ideal version of a classic mid-Victorian economy. Heavy industry developed as raw materials, power and transport links were all close by. Add on an educational system that valued practical skills and it had ready access to suitable skilled labour. However, domestic demand was low (due to lack of wages) and most production was exported. More critically, low demand meant low levels of domestic reinvestment. Devine suggests that the value of exported capital from Scotland in 1870 was £60m and by 1914 this was £500m. At the same time the Scottish economy stagnated due to lack of investment and didn't make the transition to production of consumer goods (or to light industry). Taking a step forward, by the early 1980s this meant an industrial sector that was almost a century out of date. To draw on one of Marx's insights, initially production for other producers, and export to the British Empire, masked weaknesses in domestic consumer demand. However, in the end low wages led to an unbalanced economy, especially as much investment was speculative in the search of short term gains rather for long term production. And, this is now far worse. We have a narrative where profits are seen as a reward for activity (any activity as we have the fallacy of price=value embedded by conventional economics) but wages are a cost. So business commentators will earnestly discuss this or that fall in profits but never mention the consequences of another fall in wages (apart from in the context of needed 'cost-cutting'). In reality, we need a high wage economy to sustain its ongoing development - and ability to transform to meet a new economic paradigm of resource shortage and the need to curtail excess usage. But, as in the 1890s, the needed capital goes in search of short term returns, rent extraction and capturing wealth (rather than its production). In effect, we have raised the fallacy that high wages are a consequence of a successful economy to being beyond question. The reality is that high wages are actually the basis for a successful economy. And in a Scottish context we only need to look at our own relatively recent history. If the Victorian industrialists had been less zealous in suppressing Trades Unions and wages, the Scottish economy would have developed more incrementally as opposed to becoming stuck in a model that was increasingly outdated. And, to return to Mazzucato's arguments, we need a serious discussion about what actually creates value. It really is time to leave the theories of the 1890s where they belong, in discussions about the history and development of economic thought. Since the recent general election there have been calls for the SNP Government to remove their request for permission to hold a new independence referendum. The Scottish Conservatives, Liberals and Labour Parties all argue that their relative success means there is no basis for such a new vote (of course it is also worth remembering that the SNP still have 35 out of 56 Westminster seats).

However, there are problems on both sides of this argument. The Scottish Government sought a new referendum mainly out of frustration that the UK Conservative Government was not speaking to any of the devolved legislatures. At the same time they were interpreting a narrow vote to leave the EU as a vote to exit the Single Market - a decision guarenteed to undermine the UK economy. In that context the SNP wanted to run a new independence referendum when the terms of the UK's exit from the EU were clear but before Scotland was actually pulled out of the EU. That was, and remains, a reasonable position, especially given the enduring uncertainty about the UK Government's approach and lack of confidence in their competence in any negotiations. But. The recent general election possibly has changed things. As far as anyone can work out, the UK Conservative Party remains committed to its UKIP-friendly model of Brexit with a near end to net migration and the UK out of the European Single Market. However, it no longer has the parliamentary votes to sustain this approach. The Labour Party's position remains an enigma wrapped in a black hole. Various senior politicians are pro or anti-single market and there is no real idea what they are seeking. However, I still think that in practice they will come to accept the Single Market and Free Movement (in other words EEA/EFTA terms). Which brings us to the algebra of independence. It may still be the case - mainly due to the incompetence and incoherence of the UK negotiating position - that the UK crashes ouf of the EU onto WTO terms. It is almost definitely the case that the UK Government will fail to negotiate with the devolved legislations - after all what they want still remains a mystery. So Scotland could yet be dragged ouf of the EU against its expressed will - a situation that deserves to be tested by a vote? On these grounds, the Scottish Government should not withdraw its request but should make it clear it will not progress this request as long as the UK can exit the EU onto EEA/EFTA terms. But equally, till the UK position is clear it is impractical to seek to progress this. At the moment, depressingly, it appears the Conservatives are sticking to their pre-General Election obsession with migration and fantasies as to the nature of the deal that can be agreed with the EU - but, fortunately, it is equally clear there is now no majority for this stance in the House of Commons. Which, by a round about way brings us to the algebra of independence. In particular how likelihood to vote yes or no in such a case overlaps with support for a new referendum in the short term. Broadly it is feasible to split the Scottish electorate into three groups. One (lets say around 25%) believe the only proper relationship to the rest of the UK is independence. Many of this group would support independence even if it was clear it would mean people would be worse off. On the other hand, around 35% believe that Scotland should never be independent. This group includes the Orange Order, those in the Edinburgh middle classes who do exceptionally well from the current devolution settlement and the more 'loyalist' element of Unionism (in effect the electoral coalition of the current Scottish Conservative party). This group mostly would not vote for independence even if it made Scotland better off. Fairly obviously, the 'no-never' group are not only opposed to independence but any further electoral testing of that proposition. On the other hand, most of the 'yes-of course' group would be in support of a referendum whenever it was called - though some might object on tactical grounds. The remaining 40% could be said to be persuadable either way (though most have made their minds up). Thus we tend to see support for independence shifting around the 45% achieved in 2014. But it is also this group that is more likely to be unsure about a referendum in the next few years than they might be about independence as an abstract idea. Two groups stand out in understanding why 'no, not now' seems to triumph over 'yes-,maybe later'.

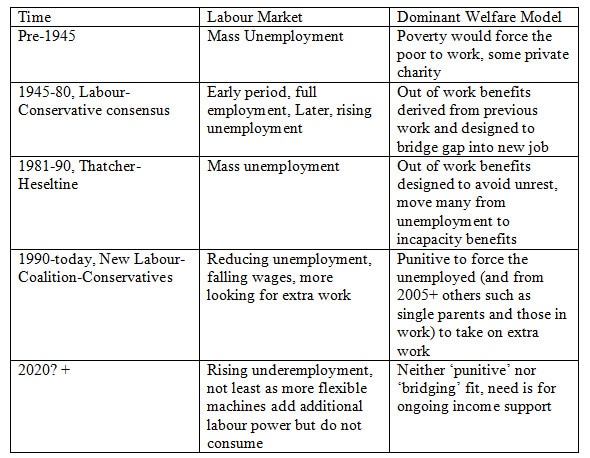

Put Corbyn, and renewed hope of exiting onto EEA/EFTA terms, together and many who might vote yes (and some who did so in 2014) in effect are saying 'not now'. But it is a caution based on possibilities, not least it is far from impossible that a weakened Conservative Government contrives a disastrous exit simply due to incompetence. But the algebra seems clear: 'Yes-of course'<''Yes now' (even if not by many) 'No-never'='No now'; 'Yes-maybe'<'Yes now' 'No but it depends' = 'No now' In effect the potential Unionist vote is against a referendum in the short term and the potential nationalist vote is divided due to the new possibilities at a UK level. So the Scottish Government would be right not to withdraw its request but well advised to make it clear that, it too, wishes to wait and see? It also indicates that lukewarm support for an independence referendum at the moment is a poor guide to voting intentions if one is to be held. So since no-one else really knows what is going to happen here is my contribution. This is more political than some blogs but then my basic interest is in Political Economy. Am quite prepared to find out I was wrong in a few days time.. BrexitSo where are we? It was clear (in so far as anything about May was ever clear) that May was aiming for a hard Brexit having fully absorbed the UKIP argument that a narrow vote to leave the EU meant a vote to exit all the structures and institutions of the EU. In particular May's refusal to accept the European Court of Justice as an arbitrar of any deal meant exclusion from the vitally important single market. If the election on 8 June said anything, it was pretty clear it is rejection of the UKIP/Tory right vision of being outside the EU. Before and during the election it was easy to poke holes in Labour's evolving, never clear, post-EU strategy. I'd suggest now that the lack of clarity is going to be rather helpful. Quite simply, the Labour Party is not really committed to any particular form of future relationship but is fairly clear about the tone and style of that relationship. So what satisfies most people - with the exception of UKIP and the Tory right? I'd suggest exit onto EEA/EFTA terms. This is simple - it already exists. Attractive to the EU, not only is it simple in form it has the advantage of not over-taxing the UK political and administrative processes. So I suspect the EU would be happy to agree that with almost no discussion. It would match the manifestos of Labour and the SNP. Even those of us who really want to stay in the EU could accept it as a valid compromise. Of interest, it would also suit the Conservatives new friends in the profoundly reactionary Democratic Unionist Party. In terms of domestic policy this grouping will reinforce every one of May's reactionary social views and profoundly authoritarian outlook. But there is one important caveat. They are opposed to a hard border between Northern Ireland and the Republic. They are also opposed to any special deal for Northern Ireland - as this will help slowly separate the province from the rest of the UK. So to them, EEA terms are ideal - no need for anything special to be done to keep a single market across Ireland. ScotlandSo where does the vote leave Scotland? First the drop in SNP MPs is not in itself particularly meaningful. Scotland is a pluralist political society with 5 parties with significant support. This is well represented in the Scottish Parliament due to the electoral system and reflected in that no local council in Scotland is controlled by a single party. Coalitions - informal or formal - are part of the Scottish political system. So a return to a pluralistic Scottish block of MPs is good. As with any major shift, there are some losses to regret. Angus Robertson will be missed as leader of the SNP group for his effectiveness in Parliament. But then some very good Labour MPs lost their seats in 2015 (among the dross). Second. A Corbyn led Labour Party standing on a sensible social democratic manifesto has posed serious questions to the SNP. It has had a relatively easy time presenting itself as bejng on the left (not hard when compared to New Labour) while governing in a very cautious centrist model. One reason for the loss of MPs was a boring campaign by the SNP and that reflects a lack of political clarity. Third. IndyRef2 now has to be off the cards for a while. If Brexit is now going to be on EEA/EFTA terms then the SNP's manifesto is met in that regard (membership of the single market/free movement of labour). This is not true of course if May manages to mess up the negotiations by sticking to her UKIP inspired stance. Four. One driver to independence was despair that the UK as a whole could not elect a government marginally to the left of the depressing mantras spouted by Blair and Brown (and the rest of the New Labour crowd). Clearly now not true. That may affect the views of many who saw independence as a pratical route to a particular goal rather than as a desired result in itself. Five. The return of the Tories means that the Scottish left must stop patting itself on the back that in some profound way Scotland is different. Their gains in the earlier local elections clearly had much to do with a very disturbing alliance with the Orange Order and the Loyalist elements within Unionism. No one wants to see those ghouls disturbed and brought back to the centre of Scottish politics. But in this election we have basically seen them pick up the parts of rural Scotland where the 'estate vote' is strong. Not only does this emphasise the need for land reform it reminds us that we do have a strong reactionary element in the Scottish body politic. So the case for independence needs to be rethought. The now derided options of Devo-max and fiscal autonomy may come back into favour. Of course if we have another general election later this year and are back to a reactionary Conservative majority - well then that changes things (again). The concept of Universal Basic Income (UBI) is gaining substantial attention recently. It has existed for some time and is often described as a policy supported by both right and left wing economists. However, this support across ideology has actually led to considerable confusion about what is really meant by UBI and how it might work in practice.. To its supporters, the logic behind UBI is compelling. It will enable citizens to make informed choices about how they allocate their time. It will provide a balance against exploitative employers who seek to leave their workers without a decent income. In addition, it will create the basis for an expansion in human creativity as people have the means to pursue long term plans rather than worry about their immediate income. The practical problem though is that UBI is actually being used to cover at least 3 very different schemes. If we are not sure which we are proposing then its implementation will be every bit as flawed as current social security and welfare systems. So lets look at the main variants and their advantages and problems. UBI as Vouchers or to replace Wages? UBI has always been attractive to the Libertarian Right. However, we need to be clear what they mean and how it would work in their approach. A key belief for this group is that, in some never explained way, competition will improve the delivery of public services and vouchers are often their preferred means to deliver this. The idea is that people will use these vouchers to buy their education, health care, and other key services. Thus when they speak about UBI what they mean is a different means to buy services that in most Western democracies are provided out of general taxation. In effect it is a rejection of the concept of univeralism and shared risks that underpins all Western European welfare states. The recent interest in UBI among the leaders of hi-tech firms and the rich and powerful who meet at Davos should be another cautionary warning. While they are responding to the threat that automation will reduce the amount of paid work available, fundamentally their interest is that a UBI scheme will reduce the amount they need to pay in wages. In effect they can transfer the cost of employment from their companies to the tax payer. There is recent UK evidence to suggest that employers will take advantage of any expected state support for income to reduce wages. Former Labour Party PM Gordon Brown, when he was Chancellor of Exchequer, introduced the concept of 'tax credits' to shore up the income of those in work but whose wages were low. The policy was badly flawed from the start with all the hallmarks of a Brown scheme. Complex, assuming the peoples' lives fitted his policy framework, the immediate effect was to land many people with limited income large income tax demands. Equally the scheme led to employers reducing wages as they shifted the cost of employment from wages to the tax payer. The result was a massive increase in the cost of the scheme. UBI as a Social Security System More recently there have been a number of practical experiments in UBI. Finland has an ongoing experiment as does the Dutch city of Utrecht. The common thread to both these, and other recent proposals such as in Scotland. is that the prime focus is on those who are unemployed. While there is consideration of how UBI will interact with waged employment, primarily such schemes aim to end the current problems of too complex welfare systems based around punitive rates of benefits. While there is a clear need for such a fundamental rethink, it is not immediately clear how such systems will really address the problem of increasing lack of work for many. The post-2008 work force is characterised not by unemployment as such but periods of under-employment and low wages. All the evidence is that this will increase due to lack of work place legal rights, weakened Trades Unions and the continued expansion of automation. In this context, UBI becomes the basis of a new model of social welfare interacting with a different world of work. For the UK since the 1930s, it is possible to track the relationship between welfare and work as: In effect UBI is a welfare model that fits a world of regular under-employment and periods of no work. It reflects the view that the punitive model has been a failure and the bridging model too optimistic as under-employment is becoming endemic.

However, it also means that employers feel they can reduce wages and there is evidence from the Finnish experiment that this is happening. While the identity of the recipients are secret, it is not hard to work out who is in receipt of UBI. Employers are treating the UBI as the first tranch of wages. In effect as with the UK experiment with working family tax credits, the known existence of state support is used to justify paying lower wages. UBI in practice We need to be clear about the emerging world of work. Wages are going to be depressed as more of the share of wealth is taken by those able to extract rents from the productive process. This means that we need a different tool to ensure that people have the income security needed to sustain a basic standard of living. As of 2016, in the UK, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation suggested this was around £17,100 per annum for a single person. To place this in context, most UBI schemes seem to suggest a payment of £1000 a month and the current basic UK benefit (Universal Credit) gives an annual income of around £4,500 (per annum). It is clear that UBI, as currently formulated, has flaws. We must reject the apparent support of the libertarian right. To them it is simply a tool to undermine what is left of universal social provision or to justify paying lower wages. Equally the current practical debate is in truth about creating a social security system that works for the emerging labour market. This is valid and much needed, but UBI was proposed as something different to social security. If it is to deliver on the hopes of its more committed proponents, there is a need to think much more carefully about the interaction of UBI, wages and work. IPPR Scotland have organised a series of events with Scottish politicians to talk about how the UK decision to leave the EU might affect Scotland. So far they have organised events with Gordon Brown, Nicola Sturgeon, and David Mundell.

The broad themes of each speaker reflected what you might expect to hear from a staunch Labour supporter of the Union, a social democrat who believes in Scottish independence and a liberal minded Conservative constrained by the lack of clarity as to UK Government policy post-Brexit. So, for Brown, the need, yet again is for a new form of relationship between the Westminster and Scottish Parliaments. As ever, listening to Brown explain why he is absolutely right, the overriding emotion is to shout 'why didn't you do that when you were in power for 13 years'? Nicola Sturgeon argued that retaining a relationship for Scotland that is as close to conventional membership of the EU is essential. In particular, the free movement of people, and inward migration, has long been accepted as key if Scotland is to have a prosperous future. While it was inevitable that her speech would be intrerpeted (by some) as simply using Brexit to push Scottish independence, I think her argument was more nuanced. The SNP were prepared to work with anyone to secure a messy deal that retained key relationships for Scotland but was also prepared to push for independence if that remained the only option. David Mundell spent most of his speech attacking the SNP for raising the possibility of a second independence referendum. Most of this was predictable and familiar but it was surprising to be told that Better Together had not argued that voting to stay in the UK was the only way to preserve EU membership in 2014. Apparently, David Cameron had given a rather obscure speech in 2013 setting out his case for a referendum on the UK's membership of the EU (this and a few other parts of his speech just came over far too much like listening to a Government press-release). In respect of the issue of the rights of EU nationals in the UK and UK nationals in the EU all gave very different answers. This did not rate a mention from Brown as he went on about his understanding of constitutional theory. Nicola Sturgeon was honest that the SNP could not resolve the uncertainty but was fully committed to free movement of people. Mundell, tried to defend the UK Government line that this an issue for 'negotiation' and was very angry to be accused of using people as bargaining chips. So, three months after the Brexit vote, we still have no UK Government policy. In turn that means any attempt to work out the best solution for Scotland is nearly impossible. But it is increasingly becoming clear that the UK Government wants to end free movement of people and, from what Mundell said, is not really prepared to work out a separate deal for Scotland. Much of the discussion in terms of the impact of new technology on manufacturing jobs concentrates on the impact of advanced robotics and improved machine learning. From this perspective, the core assumption is that manufacturing continues much as now but with a shift from human to robotic labour. In the optimistic scenarios, this will lead to lower costs, higher output (so the increased demand will generate new jobs) and overall more social wealth. More pessimistic observers tend to argue that there is no evidence that demand will expand (not least due to the uneven income distribution we already have and depressed wages) and that this will lead to a reduction in human employment. Even the IMF is now deeply concerned at the threat to wages and overall social equality. Overlooked in this focus on automation is a shift in how production itself is changing. 3-D printers are relatively new but are becoming much cheaper to run and increasingly sophisticated. Production relies on the existence of raw materials (usually but not exclusively some form of plastics) that can be cut to shape and printed – either as a complete product or then finished later in the manufacture process. The technology offers real advantages in terms of personalisation of the output (it has started to be used to produce artificial limbs etc), that it further reduces the needs to hold inventories (as new stock can literally be produced to order) and that production becomes much less dependent on large scale power sources or access to raw materials. The implications are mostly positive but with some caveats. It allows an economy to decentralise (important for a country such as Scotland with a large land area and relatively low population density). It makes it possible to manufacture in remote areas – something that is important in terms of renewable energy production where the best sites for solar, wind or wave energy production are often quite remote. At the moment, it remains a relatively technical process (in that there is a need to design and finish any item) but this maybe changing either as complete kits are available to download or standardised approaches are developed. If this does take off, the scope for SMEs (and individuals) to generate complex and substantial manufactured goods will exist. However, this reduces the costs of production and thus the ability to generate conventional profits and wages. As with the changes in information production and sharing this then raises the issue of where in a production chain can any rent or other earnings be extracted. Control of copyright may become important as this can affect both the original equipment and any designs in use, as will be supply of raw materials. So this may see manufacture shift its costs (and thus earned income) from the production process to the creation of raw materials (including power) and possession of the licences required. This in turn leads to a discussion about how work and production is organised. On the one hand, there is scope for much more shared control over the process of production, on the other hand as production costs (and thus income) fall then earning wages from the work becomes less practical. If we carry on seeing wages as a cost of production as opposed to a reward derived from that production, then the future seems to be one of increasingly precarious income for many combined with the accumulation of wealth not by those who provide the capital but by those who can find ways to erect methods to extract rent (by providing the routes for activity or via control of patents). This suggests that as opposed to allowing those who can create such gateways to accumulate the wealth there is a need to think of means to either break apart these bottlenecks or to ensure that the monies currently being accrued as rent are shared with wages. Even the IMF are now concerned that unmanaged introduction of further automation will lead to unsustainable levels of poverty. If it proves (and this maybe unlikely) that machines and humans become perfectly replaceable, then wages will fall even if overall output rises (at the least there are more ‘workers’ and the expansion of output cannot compensate). If machines can replace many jobs then at some stage wages for those in skilled (hard to substitute) work will increase in the longer term but for many wages and employment will fall. Roger Cook |

AuthorMost of the material here reflects ongoing research projects .. or just musing about the writing process Archives

September 2019

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed