|

Reading two very different books has set me to a bit of thinking. One was Mariana Mazzucato's The Value of Everything and the other Tom Devine's To the Ends of the Earth.

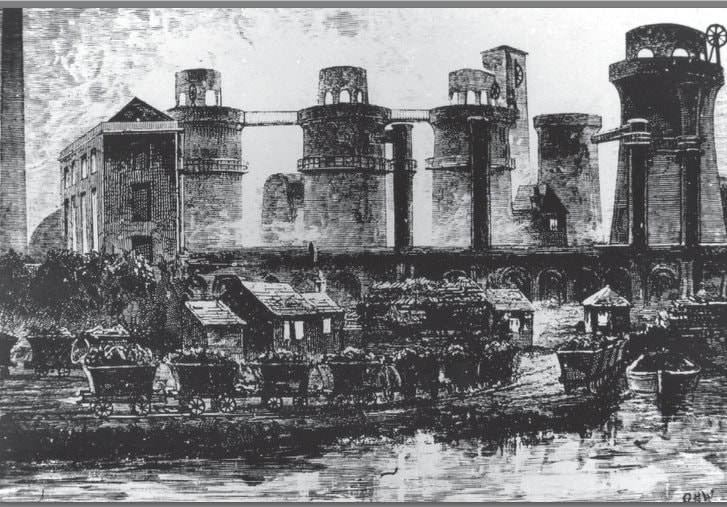

Mazzucato focuses primarily on how we define value and how this in turn defines what constitutes economic development. She rightly notes how this essential debate was deliberately closed off by the marginalist (or neo-classical) economics developed in the 1890s. This left us with no tool other than to accept that if a good, or an activity, had a price, then by definition it had value. So asset stripping, speculative investment and rent seeking are all 'valueable' purely as they can command a price. This is now so embedded in modern economics teaching that it is hard to remember the debates that dominated the profession in the period 1750-1890 (including Adam Smith) as to what was, and what was not, productive (and thus of value). Devine, at one glance, has no engagement with this debate. His book is a fascinating take on migration from Scotland and does an excellent job of debunking Prebble's lugubrious focus on the Highland Clearances. Most of the Scottish diaspora was voluntary, mainly a product of seeking to escape the low wages that were endemic in Victorian Scotland by people with some assets (note that here I am not arguing that the clearances were anything but an act of organised brutality which has left a permanent scar on Scotland) and often marked by both leaving and returning (unlike say nineteenth century Irish migration). The key issue is the impact of those low wages. Not only did this drive migration it had a catastrophic effect on the development of Scottish industry. By the 1860s, Scotland had an ideal version of a classic mid-Victorian economy. Heavy industry developed as raw materials, power and transport links were all close by. Add on an educational system that valued practical skills and it had ready access to suitable skilled labour. However, domestic demand was low (due to lack of wages) and most production was exported. More critically, low demand meant low levels of domestic reinvestment. Devine suggests that the value of exported capital from Scotland in 1870 was £60m and by 1914 this was £500m. At the same time the Scottish economy stagnated due to lack of investment and didn't make the transition to production of consumer goods (or to light industry). Taking a step forward, by the early 1980s this meant an industrial sector that was almost a century out of date. To draw on one of Marx's insights, initially production for other producers, and export to the British Empire, masked weaknesses in domestic consumer demand. However, in the end low wages led to an unbalanced economy, especially as much investment was speculative in the search of short term gains rather for long term production. And, this is now far worse. We have a narrative where profits are seen as a reward for activity (any activity as we have the fallacy of price=value embedded by conventional economics) but wages are a cost. So business commentators will earnestly discuss this or that fall in profits but never mention the consequences of another fall in wages (apart from in the context of needed 'cost-cutting'). In reality, we need a high wage economy to sustain its ongoing development - and ability to transform to meet a new economic paradigm of resource shortage and the need to curtail excess usage. But, as in the 1890s, the needed capital goes in search of short term returns, rent extraction and capturing wealth (rather than its production). In effect, we have raised the fallacy that high wages are a consequence of a successful economy to being beyond question. The reality is that high wages are actually the basis for a successful economy. And in a Scottish context we only need to look at our own relatively recent history. If the Victorian industrialists had been less zealous in suppressing Trades Unions and wages, the Scottish economy would have developed more incrementally as opposed to becoming stuck in a model that was increasingly outdated. And, to return to Mazzucato's arguments, we need a serious discussion about what actually creates value. It really is time to leave the theories of the 1890s where they belong, in discussions about the history and development of economic thought. |

AuthorMost of the material here reflects ongoing research projects .. or just musing about the writing process Archives

September 2019

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed